Many gardeners, market gardeners, and farmers may be using compost as a fertilizer, but is it actually a fertilizer, and does it have the nutrients plants need? Technically it is a fertilizer, and you can read about that in my article here if you would like. It does contain the 3 primary nutrients nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, as well as many other nutrients, but how much? How much nitrogen is in compost, and how much will be available to your plants?

Typically, a well made compost can have a nitrogen content up to 4.5%. This is dependent on the compost material, the type of composting that was used, and the age of the compost.

This is for compost made in the hot compost method, which is what most of the information in this article is about. The same nutrients will be available in other composting methods but may very in percentages. Lets take a look at the nutrients in compost in a little more detail though, just for fun.

How much nitrogen is in compost, and is it available to plants?

The amount of nitrogen in compost will vary depending on many factors during the composting process. The composting process whether it be cold or hot, the material added for composting, water and aeration, processing and storage time, and the carbon to nitrogen ratio all play a part in the available nitrogen that is left in finished compost.

Fully mature compost can have a nitrogen content in the range of 0-6%. This largely depends on the feedstock (the material being composted) used and how well the composting process and storage is managed. With high nitrogen feedstock the likelihood of the finished compost to have a higher nitrogen content is increased.

The table below shows some information from different sources and the varying amounts of nitrogen that was found in compost samples tested, or the typical ranges expected in compost that will be tested.

| Source | Nitrogen Content |

|---|---|

| A & L Canada Laboratories | 0% – 6% |

| Montana State University Extension | <1% – 4.5% |

| Washington State University | 0.4% – 3.5% |

| Oregon State University | 1% – 2% |

As you can see the levels of nitrogen in compost can vary quite a bit. This is because compost is not a standardized product like synthetic fertilizer, it is the result of natural processes. We cannot fully control how the microbes in the compost will behave. We can only give them a favorable environment for them to live in. If the compost has done a good job at providing that, then it is more likely we will have a good compost in the end.

In general though, feedstock that contains a high nitrogen source like manure, grass clippings, weeds, etc, will produce a compost with higher nitrogen content than a compost made with mostly hay or wood chips/sawdust. Not to mention a compost made of only wood chips/sawdust would take forever to fully compost. That can put a damper on your home composting if you need to wait for years to use your own compost.

Why does the nitrogen content go down during composting.

Nitrogen in compost is used by microorganisms in the compost pile during their life cycle. They use the nitrogen for their cell structure and the carbon for their energy source. The nitrogen is used by the microorganisms and when each one dies the nitrogen that was stored in their cell material is used by a new microbe, so the nitrogen is basically recycled. This does not mean that nitrogen in the compost is not lost, it can be lost but that loss can be reduced by properly managing the compost.

The carbon on the other hand decreases with time as the microbes use it for energy and then release much of the carbon in the form of CO2 (Carbon Dioxide). This causes the carbon content in the compost to go down because carbon dioxide has “carbon” in it, and it will just float away. This will continue and then eventually slow down over time as most of the remaining carbon in the compost is tied up in materials such as cellulose and lignin. These materials are hard to break down by the microbes that thrive in the hot portion of the composting process. At this point things like actinomycetes and fungi take over most of the composting process that is left.

The nitrogen in the compost will hopefully be recycled as much as possible and we can keep as much in the compost as possible for use in the garden or field. Conservation of the nitrogen can be improved if a proper C:N ratio is used in the composting process.

Carbon to nitrogen ratio in compost, and nitrogen retention.

Nitrogen can be lost during the composting process for many reasons but that does not mean that the loss of nitrogen can not be limited in some way. One important way to minimize nitrogen loss during composting is by maintaining a carbon to nitrogen ratio that has been shown to minimize nitrogen loss.

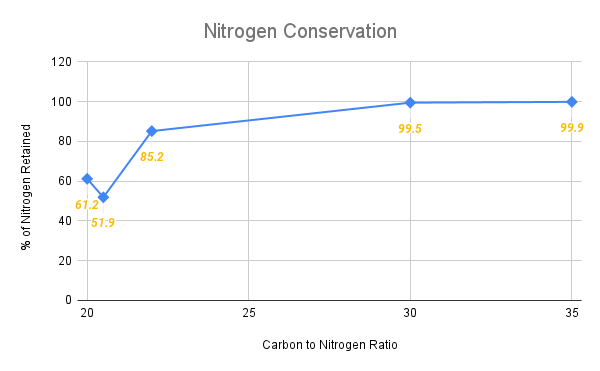

Nitrogen loss in during composting can be minimized by maintaining a proper C:N ratio, with ratios of 26:1 to 38:1 being optimal. If other nitrogen reducing factors are controlled such as leaching of nutrients caused by rain, these ratios can lead to a nitrogen retention in finished compost of over 90%.

As you can see from the chart above the nitrogen retention in finished compost goes up as the C:N ratio in the initial composting material goes up. Meaning that the more carbon we put in the compost pile in the beginning, less nitrogen will be lost during composting. This means more of the initial nitrogen will be available in the finished compost. So maximum retention can be obtained with higher initial carbon content with a target C:N ratio between 26:1 – 38:1 being ideal.

It should be noted that as C:N ratios in the initial compost material (feedstock) go above 40:1, there is a decreasing trend in nitrogen retention. Unfortunately the source for the data used to make the graph above did not have the data needed above a 40:1 ratio. It was mentioned that above 40:1 the nitrogen retention will decrease, but they gave no data for it, strange. I think the lesson is to try and get a ratio between 26:1 and 38:1, and anything close to that is just fine.

When the carbon to nitrogen (C:N from now on) ratio is to low, meaning to much nitrogen for the amount of carbon available, nitrogen retention starts to decrease substantially. This is because the microbes in the compost will consume the available nitrogen, use what is needed, and release any excess nitrogen in the form of ammonia into the atmosphere. This gives crappy (pun intended) compost that wonderful eye watering smell that we all love so much. I don’t love it, I really don’t.

For a list of C:N ratios of different compost materials check out my list I compiled for you here.

Availability of nitrogen in compost.

We have already established that compost has nitrogen, not an incredible amount but it is still has nitrogen. How available is this nitrogen though, is it available at all? Is it used up quickly or released slowly over time?

Most of the available nitrogen in fully matured compost has become bound to organic compounds that are fairly resistant to decomposition. This makes the release of nitrogen in compost for uptake by plants a slow process which can last and entire growing season or more.

According to the University of Massachusetts Amherst the amount of nitrogen in finished compost that is tied up in these organic compounds is usually 90% or higher. Of this nitrogen only 10%-30% are available in the first season. The rest will slowly become available as the material continues to break down in the soil. This will act like a slow release fertilizer, a very slow release fertilizer.

What about other nutrients in compost? Does compost contain potassium or phosphorus?

What about other nutrients in compost, does it contain things like phosphorous, or potassium? Are these nutrients at a level high enough to have any beneficial affect. If so how much does it contain?

Finished compost can have an expected value for phosphorous and potassium in the range of 0.3% – 3.5% and 0.5% – 1.8% respectively. Phosphorus in finished compost can be less available that potassium as much of it is bound to organic matter in the finished compost.

| Source | Phosphorus | Potassium |

|---|---|---|

| Washington State University | 0.3% – 3.5% | 0.5% – 1.8% |

| Montana State University Extension | 0.8% – 1% | 0.5% – 1% |

| Oregon State University | 0.3% – 0.9% | 0.5 % – 1.5% |

As you can see just as before, the nutrients can vary quite a bit and this can be expected. According to the University of Oregon if phosphorous is above 0.7% the compost likely contained manure as a feedstock. Likewise, if Potassium is above 1.5%, the compost likely had manure, food waste, or grass clippings as a feedstock.

Not that either of these nutrients being higher is a bad thing but if you know your compost is made with manure you can expect these two nutrients to be higher.

Phosphorus as noted above can be largely unavailable to plants in finished compost as it is bound to organic matter in the compost. When the compost has been incorporated into the soil, this phosphorus can be released from the organic matter by microbes in the soil, but still not available to plants for uptake. This is because the phosphorus can become bound once again to elements in the soil.

According to the University of Massachusetts some studies have shown that plants can actually suffer from phosphorus deficiencies if they are grown with compost as the only fertilizer source. In the long term this phosphorous may become available but for short term growing, compost may need to be accompanied by some other sources of phosphorus.

Potassium in finished compost is much more available and is not bound like nitrogen or phosphorus can be. It is water soluble so the compost should be monitored and not allowed to sit in wet conditions or exposed to rain. This can cause leeching and some of the potassium can washed out of the compost.